Deaconess Sister Silvia approached me in 2014 to ask whether I would consider making a film about her family history. Her (Swiss!) grandfather had been a concentration camp commandant in Nazi Germany, something that cast a dark shadow all the way into the present and that affects her to this day.

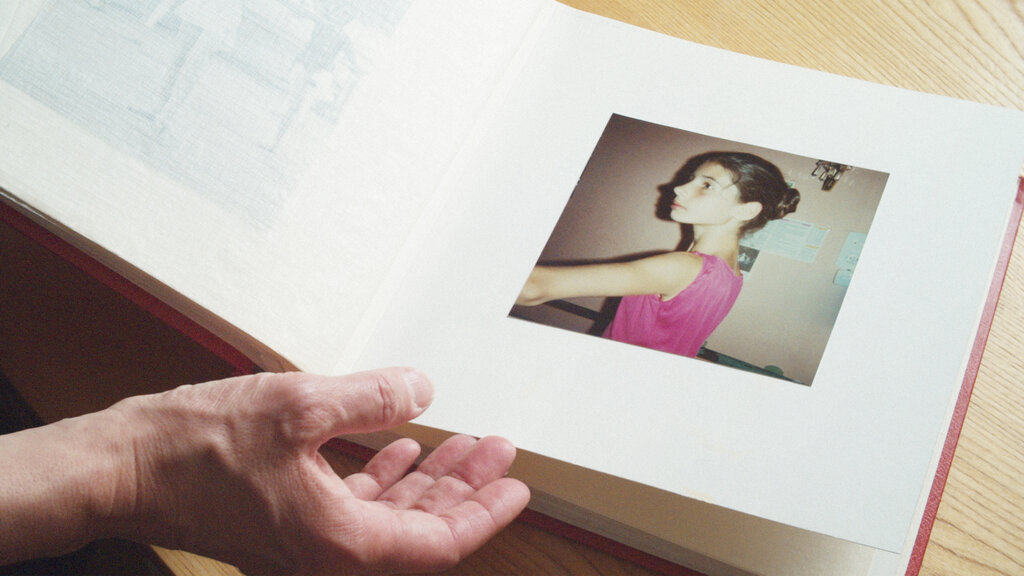

I got to know Silvia through her creative side. She had trained as a dancer when she was young and regularly organizes dance workshops. It was her idea to create a series of performances on the premises of the former concentration camp.

I was fascinated by both her story and her personality. But I wanted to create a truthful portrait of her, not serve up a film to be her mouthpiece. We agreed that I wouldn’t be making a commissioned film. It would be a real documentary, I would be its director, and Silvia would give herself over to the process.

Neither of us had the slightest idea of the journey that awaited us. Another story was behind that of the grandfather, waiting to be revealed: a painful tale of abuse.

That is the fascinating thing about non-fiction film, especially of the long-term observational kind. The script for this film wasn’t written by me, and what happened far exceeds anything Silvia could have foreseen. It touches upon the mystery of fate.

“The Third and Fourth Generation” was produced without any state funding or TV participation, with a minimal budget (about CHF 20'000).

I accompanied Silvia longer than was originally planned, from 2016 to 2019. At the end of those three years she made a life-changing decision that I won’t disclose here. I make an appearance in the film as its director to ask the protagonist whether the film project influenced her decision in any way. She answers with a straight yes.

This raises an ethical question. Shouldn’t a documentary film show life as it is, without interfering in any way? Is it legitimate to intervene as a filmmaker? In actuality, filming a life already means acting upon it. In other words, a documentary film always affects the life of its protagonist(s) to a certain degree. The traditions of the essay film and Cinéma Vérité, to which this film belongs, seek transparency and draw the person behind the camera into the story. As a filmmaker, I’m not only interested in telling a powerful story; I’m not a cold, detached camera, but a companion.

“The Third and Fourth Generation” is influenced by the Polish school of documentary. We opted for long, carefully constructed shots and a slow editing pace. The austere beauty of the scenes and images are an invitation to contemplation and spiritual reflection.

Lukas Zünd, director